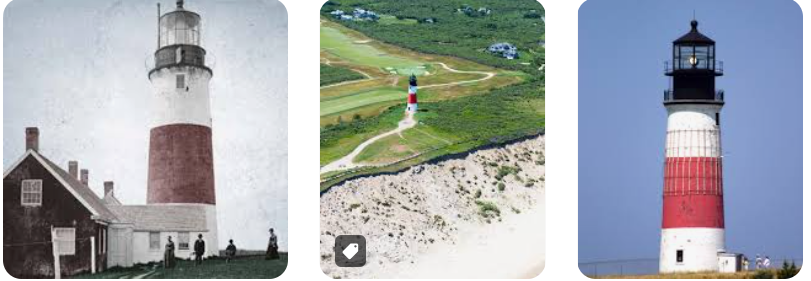

Sankaty Head Lighthouse

Where the Land Gives Way

https://youtube.com/shorts/1AuOHRUEmjE

Perched on the eastern edge of Nantucket, Sankaty Head Lighthouse stands like a quiet witness to erosion, exile, and endurance. It is not a lighthouse that dominates the sea—it watches it retreat and return, year after year, grain by grain. Few lights in America have been forced to confront the impermanence of land itself quite so intimately.

First lit in 1850, Sankaty Head was built to guide ships through the treacherous waters off Nantucket’s shoals—a graveyard of wrecks shaped by fog, currents, and sandbars that shift without warning. The lighthouse’s red-brick tower rose 70 feet above the bluff, its light visible for miles, a steady presence for mariners navigating uncertainty. For generations, it did exactly what it was meant to do: hold its ground and shine.

But the land beneath it did not share the same loyalty.

Sankaty Head sits atop a clay and sand bluff that has been slowly surrendering to the Atlantic for centuries. Wind, waves, and storms gnawed at the cliff face long before the lighthouse ever arrived. By the late 20th century, the erosion had become impossible to ignore. The ocean was no longer a distant companion—it was advancing with intent. Each year, the bluff lost several feet. The lighthouse, once comfortably inland, crept closer to the edge.

By the early 2000s, Sankaty Head was in real danger. The cliff was retreating at a rate of nearly one foot per year. At that pace, collapse was no longer a hypothetical—it was inevitable. The question was no longer if the lighthouse would fall into the sea, but when.

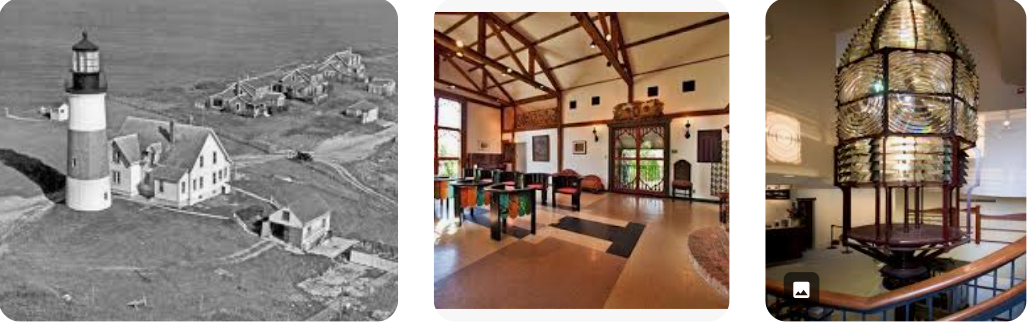

In 2007, the unthinkable was done: Sankaty Head Lighthouse was moved.

In a carefully orchestrated operation, the entire structure—tower, foundation, and all—was lifted and relocated approximately 400 feet inland. It was a moment heavy with symbolism. Lighthouses are meant to be fixed points, anchors against chaos. To move one feels almost like admitting defeat. And yet, it was also an act of preservation—of respect for history rather than stubborn pride.

The move saved the lighthouse, but it did not end the story.

Today, Sankaty Head still stands on a bluff that continues to erode. The Atlantic has not been tamed; it has merely been delayed. The lighthouse remains operational, automated, and still serving its purpose, even as the land beneath it remains transient. It is a reminder that human structures—even the most enduring ones—exist only by negotiation with nature.

There is something quietly haunting about Sankaty Head. It does not loom over crashing waves or dramatize its presence. Instead, it stands slightly back, as if aware of what the sea is capable of. It is a lighthouse that understands loss—not through shipwrecks alone, but through the slow disappearance of the ground it once trusted.

To stand near Sankaty Head is to feel the tension between permanence and impermanence. The light continues to shine, steady and indifferent, while the earth beneath it inches away. It is not a monument to conquest, but to adaptation. A lesson written in brick and clay: sometimes survival means knowing when to move.

And still, each night, the light turns.

Not to challenge the ocean—but to coexist with it.

#SankatyHeadLighthouse #Nantucket #HistoricLighthouses #CoastalErosion #MaritimeHistory #VanishingLand #AtlanticCoast #SeaAndStone #LighthouseStories #AmericanMaritime