Stone remembers what people forget

Salisbury Cathedral does not announce itself with grandeur. It rises instead — slowly, deliberately — from the English plain, as if the earth itself decided to grow a monument.

Built beginning in 1220, Salisbury Cathedral is one of the purest surviving examples of Early English Gothic architecture. Unlike many medieval cathedrals that grew in fits and starts over centuries, Salisbury was constructed with unusual speed. In just 38 years, the main structure stood complete. That efficiency left behind something rare: architectural unity. One vision. One voice in stone.

It remains mind-boggling that this immense and intricate cathedral was built by people traveling by horse and buggy, using hand tools, patience, and faith rather than modern machinery.

But unity does not mean simplicity.

The cathedral’s spire — added later in the 14th century — reaches 404 feet into the sky, making it the tallest church spire in England. Medieval builders never intended it. The original foundations were far too shallow for such ambition, laid in marshy ground near the River Avon. The spire’s weight caused the structure to shift, bow, and strain almost immediately. Iron tie rods, buttresses, and internal reinforcements were added over centuries — quiet acts of engineering desperation holding faith upright.

Inside, light pours through tall lancet windows, pale and controlled. This is not the riot of color found in later Gothic cathedrals. Salisbury’s beauty is restraint — a kind of holy discipline. Stone columns rise like bundled reeds, emphasizing height over mass. The eye is constantly drawn upward, toward the ceiling, toward the idea of heaven rather than its decoration.

And then there is the document.

Salisbury Cathedral houses one of the four surviving original copies of the Magna Carta, issued in 1215. It sits not as a relic of freedom, but as a reminder of tension — between king and church, power and conscience, authority and restraint. The Magna Carta was never meant to be democratic in the modern sense. It was a contract among elites. Yet its survival here is symbolic: law sheltering beneath faith, and faith entangled with governance.

Time has left its marks everywhere.

The cathedral clock, dating from around 1386, is considered one of the oldest working mechanical clocks in the world. It has no face. No hands. It was never meant to be seen — only heard. Time, measured for monks, not for crowds. Bells told the hours; obedience followed.

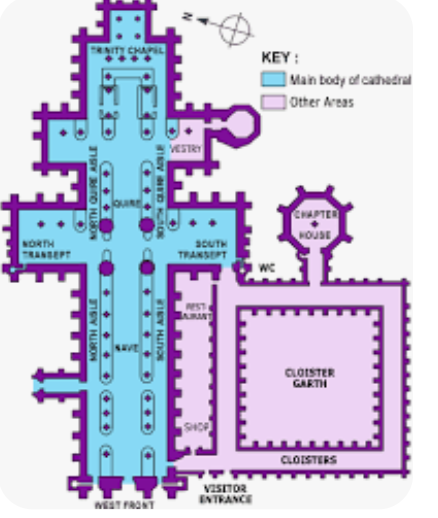

Outside, the cloisters form the largest medieval cloister walk in England. Wind moves differently there. Footsteps echo. Even today, the space feels like a threshold — not fully inside, not fully outside. The kind of place where decisions linger.

Salisbury Cathedral has survived war, reformations, political upheaval, and neglect. It has leaned. It has cracked. It has been patched and propped and prayed over. Yet it stands — not perfect, not untouched — but enduring.

This is the Gothic truth the cathedral teaches quietly:

Faith does not eliminate strain.

Belief does not remove weight.

Structures survive not because they are flawless, but because someone keeps tending the fractures.

Stone remembers. And Salisbury still speaks.

#GothicDustDiaries #SalisburyCathedral #GothicArchitecture #DarkHistory #MedievalEngland #SacredStone #HauntedHistory #AncientPlaces #Cathedrals #TimeInStone #HistoricEngland #MagnaCarta